Glazed domes and leaded lights

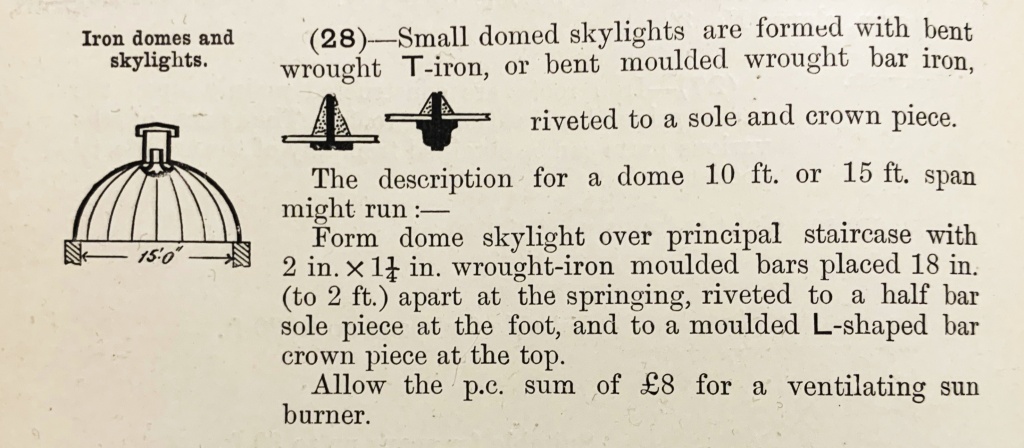

Glazed domes feature widely in Carnegie libraries, although partly facilitated by an increasing availability of patent glazing bars, it is also evident from the detailed drawings for Possilpark Library and from the following entry in Specification of 1898, that they might equally be “made up” using bent wrought iron “T” sections.

Such rooflights are particularly vulnerable to leakage and the practice of creating a double skinned assembly with an inner decorative filter concealing a weather-proofed external layer of glazing as is visible in the small dome at Burnley.

The lending section of Stockport library has the largest glazed dome of all the Carnegie Libraries in the UK, measuring approximately 10.5m in diameter. As with the second largest glazed dome at Rutherglen, the decorative leaded lights of the interior dome are protected by a secondary roof which used curved patent glazing above it, as is detailed in extensive illustrations in the publication of the winning competition design Building News 9.12.1910. The purpose of leaded lights in these domes was not simply decorative, they were used to diffuse the brightness of sunlight and so maintain visual comfort.

Leaded lights were also extensively used both decoratively and pragmatically in glazed partitions, since they offered the benefits of illumination whilst maintaining privacy. Fratton library, below, has an excellent range of these all still in tact and using both stained glass and textured glasses.

The tradition of lead glazing is most directly associated with stained glass windows in churches and the translation of worthy instruction where they are incorporated in public libraries is common. Such as in this staircase windows at Ayr library below. Importantly the narratives depicted in church windows and in these ones are illuminated for the people at eye level inside by heavenly light from outside. However, notably at Ayr, at the top Carnegie’s initials are intended to be read from the outside.

In Carnegie libraries, with the advent of safe artificial light, the messages could be reversed, as seen here. The logo for this website is derived from a similar stained glass motif at Mount Washington Library in Pittsburgh. There is further discussion of the self-deifying ambition of Carnegie who desired the phrase “Let there be light” to be used widely in earlier work.